Since Brianna Rader started to build a sex-ed app about a year ago, she has spent many afternoons staked out in suburban shopping malls.

The many conversations she's had with teenagers there, in food courts and near American Eagle stores, have taught her a lot about how they talk about sex, and how they talk in general: Apps with menu navigation bars seem archaic. Fruit, like eggplants and peaches, stand in for anatomy in text messages. "Box" is slang for vagina. Peers' experiences with sex are interesting. Anything called "sex ed" is not.

The result of all these conversations, an app called Juicebox, launched on Thursday.

Juicebox has company in its strategy of delivering sexual health information via mobile phones, where teenagers communicate most often. The California Family Health Council (CFHC), for instance, launched a statewide program in 2009 that distributes weekly sexual health tips to teenagers through text messages, and the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power and Potential has made an app that locates nearby sexual health services and provides information about birth control.

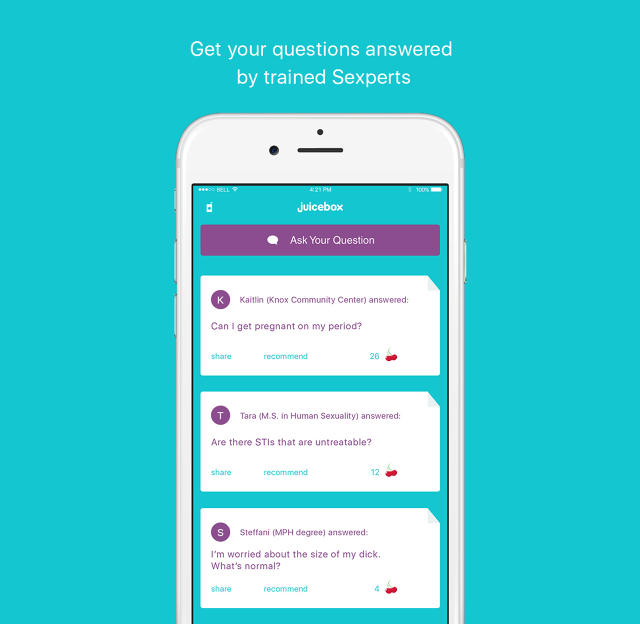

But Rader's app sets itself apart by making every effort to function less like a pamphlet about STDs and birth control than a fun product like Snapchat. At launch, it has two features. One, which users can access by swiping left, is called "Snoop" and allows teenagers to ask questions of sexual health professionals, who are each members of the Association of Sexuality Educators, Counsellors, and Therapists. When Rader tested the feature, she found that teenagers were just as excited to browse questions others had asked. Among questions the beta testers submitted are standard sex-ed fare like, "Where can I get an STI test?" and "Can I get pregnant on my period?" But the open-ended format also lends itself to questions that are hard to imagine in a P.E. teacher's annual sex-ed PowerPoint: "How big is the right penis?" and "How do I have sex with an uncircumcised guy?"

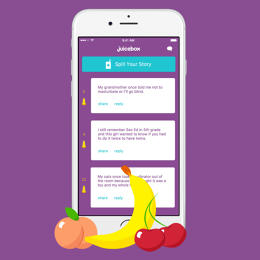

The second feature, "Spill," asks users to share their own stories about relationships and sex. Other users can upvote these stories by tapping a condom icon next to each one. In a detail that could be either hilarious or horrifying, depending upon your attitude toward sex and sex education, the condom icon grows when touched. "Our tagline is, 'Avoid all the awkward,'" Rader says. "It's not, 'Here's a sex-ed app.'"

Rader, who is 24, grew up in Tennessee, where public schools teach abstinence-only education and parents can sue schools for promoting "gateway sexual activity." She started Juicebox-which was called "Hook Up" until teenagers told her that name was intimidating-after a republican state senator launched a campaign against a sex education organization she started while studying at the University of Tennessee. "I learned that sex ed in America is a public policy battle," she says, "and it's going to take a long time. It involves talking to teachers and schools and parents and unfortunately state legislators, and I just wanted to build a disruptive tool that could get the information faster to the people who need it."

The United States has high rates of STD and HIV infection among adolescents, and, among industrialized countries, the highest rate of teen pregnancy. Teen pregnancy rates are typically higher in conservative southern states that do not mandate medically accurate and comprehensive sexual education.

As of last year, 22 states require that schools teach sex ed. Only 19 states require that, if provided, that education must be medically accurate.

Rader, who finished her master's degree in global health last year, began the project that became Juicebox by asking teens and young adults where they learned about sex. The top three answers were friends, Google, and movies. ("You can interpret 'movies' however you want," she notes.) When she had a prototype of a website, she presented it to her mall beta testers as just another type of media from which they could learn that involved their peers. As the site became an app ("Some of them even write their English papers on their phones," Rader says. "It's just what they're used to"), Juicebox stuck to this goal of creating a social app about sex and relationships-albeit one seeded with health professionals who provide medically accurate information.

The possible advantage of this strategy is twofold. One, Rader hopes that inserting information into an entertaining format will increase the chances that teenagers, young adults, and anyone else who wants to learn about sex will actually use the app, which has a draw similar to the Q&A and "embarrassing stories" sections of a women's magazine. The other is that Juicebox doesn't plan to rely on donations. Like any social app, the for-profit company will make money through some mix of advertising, sponsorships, and premium features. An early version of the idea contained games like "Sperm Invaders," in which players shoot birth control pill packs and condoms to kill sperm before it reaches the egg.

"Our app is entertaining and fun first," Rader says, "education second." If all goes as she hopes, putting education second could actually be the best way to put education first.

No comments:

Post a Comment